Part 1 of 2 about my experience with alternative grading this semester, focusing on what’s working well. In Part 2, I’ll address some of the challenges and questions it’s prompted.

I’m teaching a research course this semester, and, in the hopes of showing students that research is something that people actually do, regularly, in their day-to-day jobs, I’m conducting a little experiment of my own: doing away with letter grades, with the exception of the required midterm and final course grades.

This isn’t coming out of nowhere. I started taking baby steps in this direction a couple of years ago, as a high school teacher, when I first started allowing revisions of essays with no penalty. Last semester I did away with grades for formative assignments, grading only students’ participation and their four major writing projects. And I’ve been following along with other educators’ experiences, mostly here on Substack (namely, Unmaking the Grade and Grading for Growth), and engaging in conversation with writing instructors at BGSU who use contract grading in place of traditional grades.

But it still feels like a big, uncertain leap. And so I’m glad that it’s taking place in the context of a research class, where I can pitch this grading experiment to students in a framework that we’re collectively invested in this semester—starting with a genuine question, reading broadly to see what others are saying, collecting primary data, and then trying to make sense of it all.

Most of my students are in that messy middle part of their research projects right now, that point where you’re awash in sources and starting to lose the thread of your research question, when you feel like things should be coming together, but they aren’t quite.

And I feel right there with them. We have two weeks until spring break—which is to say, two weeks until we’re at the midpoint of the semester—and I feel conflicted, intrigued, torn about this (non)grading system I’ve committed to.

So I wanted to pause, take stock, lay out what’s working and what maybe isn’t; what questions feel answered and what new questions have cropped up. I’ve found it comforting to continue reading about other educators’ experiences with alternative grading as I try it out myself (such as this post from earlier this week by Stephanie Kratz on “Ungrading in Real Life”). I have a knee-jerk reaction against innovations in education that promise to solve all the problems (Just do this and you’ll never have to grade past 5 again! Make this change and your students will be engaged, motivated! If you teach in this way, learning will always be authentic and never forced!) And so it’s been refreshing to read reflections and advice that are precisely not that—that balance genuine enthusiasm about the changes they’ve adopted with continued questions and critiques of their approaches. Most of what I’ve read about alternative grading has been directly from educators practicing it themselves: They speak with clarity about why they are eschewing grades, but remain critical, reflective, and real about its drawbacks and challenges.

The main trend I’ve noticed is that most of the educators writing about alternative grading have not found a single approach and stuck with it. They’ve continued to tweak their practices each semester or year, keeping what works and playing around with what has left them unsatisfied. The way that any good educator does with any part of teaching: curriculum, instruction, and, yes, grading.

So my “research”—in so far that this is research—is the unexciting but necessary kind, a replication of what other people have already tried in a new setting.

What’s working.

Writing and research lend themselves well, not just to alternative grading as a practice, but to discussions about it. So far, alternative grading has been a helpful touchstone to return to whenever I’m modeling the research process in class. Students are mostly working on individual projects, but this is supposed to be a seminar class, grounded in discussion. While they can certainly share experiences and ideas from their projects with one another, it’s been useful to have a shared topic and question that we can return to as an example—an example that everyone is at least somewhat invested in.

I started the semester with an ice-breaker activity suggested by Robert Talbert, in which I asked students to identify one thing that they were good at and how they became good at it. Students entered their answers in PollEverywhere, which produced a word cloud showing the most common words in the largest font. The class results were as Talbert predicted: practice and repetition.

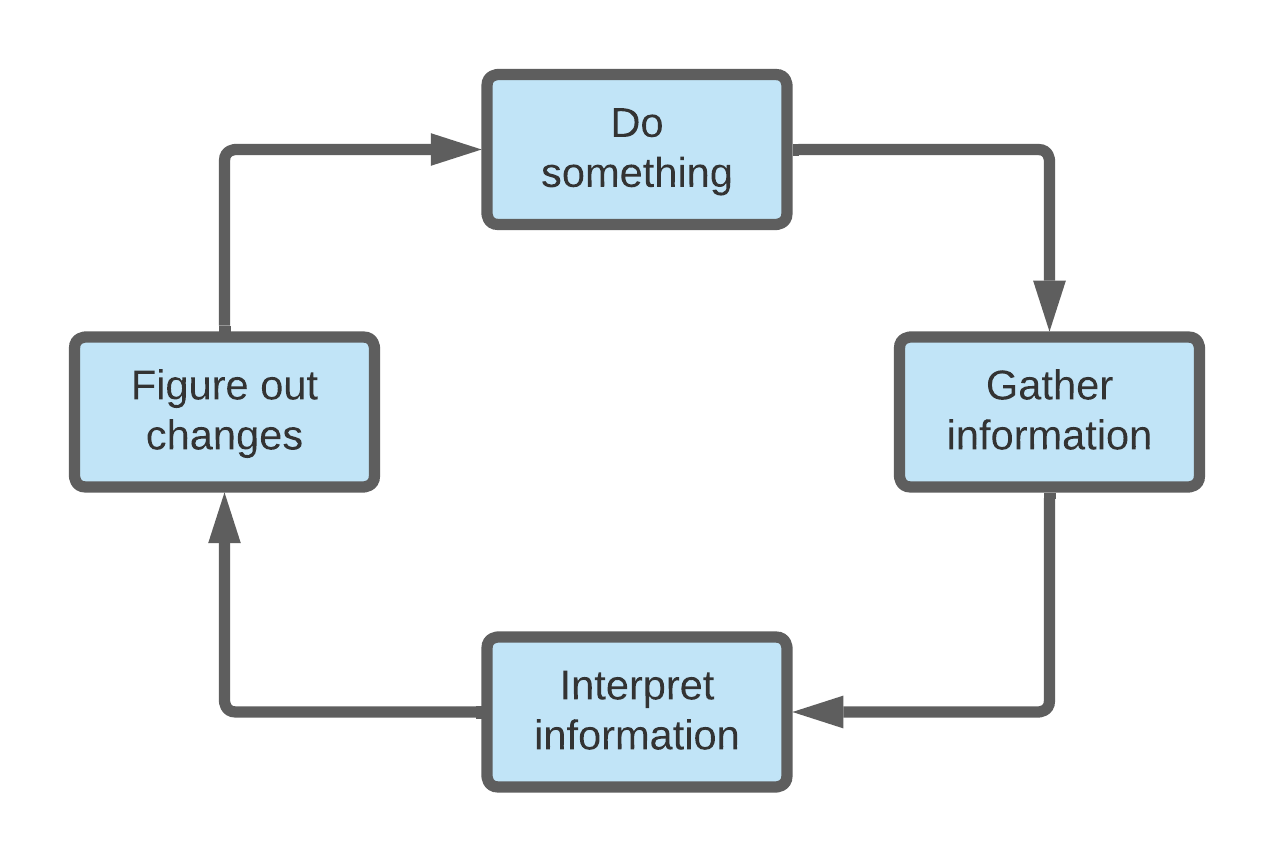

We spent some time in class discussing the “feedback loop”: why it’s an important part of both writing and research, how grades may interfere with that process. If you know you’re going to be graded for early stages of writing and research, you may be less inclined to take risks; there may be less incentive to go back and revise.

During the first week of class, students read Alfie Kohn’s “The Case Against Grades” and a piece titled “So Your Instructor Is Using Contract Grading.” Then we broke down the arguments in the articles, identifying what they were arguing and why, what counterarguments they identified and how they did (or didn’t) respond to them. I had students write a discussion post reflecting on their own thoughts about the articles and the concept of alternative grading, and then told them, honestly, why I was trying it this semester: namely, that research begins with a question you genuinely don’t know the answer to but that you are invested in exploring.

We’re been returning to this question whenever we reach another stage of their research process. The first core assignment of the course was an “Initial Project Description,” in which students identify a research question and explain its significance. I created a model with my question and rationale. Later, after students had gathered at least five secondary sources related to their question, we did an activity in which they mapped out how these sources were in conversation with one another. I returned to my grading question to show how I’d map a conversation between my sources. We went back to Kohn’s article together, looked at where he was citing other studies, and talked about the scholarly conversation.

This week, as students move from secondary research into primary research, we’ve begun discussing surveys, interviews, and observations. For our survey discussion, I created a “bad survey” with questions about grading that illustrated some common errors (leading questions, double-barreled questions, jargon-heavy questions, etc.) Students met in groups to view the survey, identify the problems, and offer feedback on how I could improve my questions.

Tomorrow, we’ll do an activity with interviews, brainstorming who I could interview about alternative grading and what questions I could ask. Students will pair to interview one another about their experiences with grading so that they can practice asking follow-up questions and taking notes.

In sum: the grading experiment feels like an authentic way to engage with and illustrate the research process to students. I know, already, that they have a spectrum of feelings about the lack of grades. Some seem to like it; others prefer the structure and familiarity of traditional grades. This variety of views has been helpful: it means that when we talk about alternative grading, it’s a genuine conversation. It means that every time I pose my research question to them, it’s obvious that it doesn’t have a clear answer—for our class as a whole, or for me as an individual instructor.

Of course, it hasn’t all been smooth and clear—that’s part of the point. More on the particulars of that in Part 2, but for now, suffice to say: the process of trying has been fruitful.