Part 2 about my experience with alternative grading this semester, focusing on challenges and questions. Part 1 focused on what’s been working well.)

There’s an unavoidable kind of guilt I think most teachers have. If not most, then many. And I count myself among them.

It goes something like this: I want to be a better teacher, which means trying new things. Sometimes these new things work, and sometimes they don’t.

When they don’t work, the guilt extends towards my current students. When they do, towards my former ones.

With grading this semester, my guilt has been oscillating between these two poles.

In so far as alternative grading has been going well, it’s been prompting me to look back at my first years of teaching and feel a bit of a drop in my stomach. This isn’t new. My grading practices have changed gradually each year, so I often think about my early years of grading in this way.

The very first assignment I ever graded is still quite fresh in my mind. It was a book review, for summer reading assigned by the teacher before me. The first week of class, I gave students a rubric, explained the difference between a review, an analysis, and a summary. Students wrote the book reviews and turned them in. I graded them and turned them back. And I remember giving one student a D.

This wasn’t the lowest grade I gave. Some students hadn’t read the book at all. Or didn’t write the review. And it wasn’t the only D I gave. But I remember this student in particular.

She’d clearly read the book. She summarized it well. She’d written clearly. But that was all: no evaluation, none of what we’d just talked about with regards to a book review. And I felt stuck: my rubric, written before I’d read any of the students’ writing, written with hypothetical papers in mind but no real ones before me, and no experience to help me guess at the kinds of common errors that might crop up, clearly placed a paper that “just summarized” at the D level.

Call it a problem with the rubric. Call it a problem with my inability to pivot when I received a paper that didn’t match what I’d anticipated. Call it a problem with my grading philosophy in general. But it’s clear to me looking back that in whatever framework I devise, this wasn’t the grade I wish I’d given that paper.

I’m not without sympathy for my young teacher-self. I was 22. I was doing my best. I had a misconception lodged in my brain that it was good to be tough on the first assignment so that students take you seriously. I wanted to challenge students. I wanted to be fair. I thought I was doing both.

But later that year, I would think back to this grade sometimes and physically cringe. Wondering if I’d killed that student’s desire to write. Her love of reading. Her sense of her own abilities as an English student.

She ended up doing well in the class. I hope that the first harsh grade of the semester faded into the back of her mind, that she never thought about it again. But I kind of doubt that it did. And it’s seared into mine.

And so when I stop to think about how far I’ve swung in the other direction (before this semester, but particularly this semester), I have this immense guilt towards my past students. Students who experienced me as a harsh grader, as someone who thought that low grades would motivate a person, who did not create much space for revision. I wonder: If I’d graded differently, taught differently, what would have been different for them?

But I’m also not sure that what I’m doing right now is good. If I’m serving my current students well. I have mixed feelings about alternative grading (more on the specifics below), and I’m not sure, at this point, if I’ll use a similar approach next semester. And so I feel an anticipatory guilt towards my current class, who did not sign-up for this “experiment,” who might not like it, who might feel cheated by it.

This is inevitable with any kind of change. I point it out not because I think I should or shouldn’t feel guilt (the should doesn’t matter; I just do) but because accepting that I will feel that way seems important. The alternative is not to try anything new at all. And what kind of hypocrite would I be if I challenged students to take risks in their writing but remained in the safe stability of adequate-and-familiar teaching myself?

The thing with trying something new in the classroom is that you are bound to be wrong. It’s unavoidable. Either your past or your current self or (somehow) both. It’s humbling, and humility is good in a profession where it’s so easy to become, as the phrase goes, “the sage on the stage.”

But it’s also good for that humbling wrongness not to become the only note. Teachers are so often expected to be everything—to solve all kinds of social problems, to not only teach but to motivate, to not only motivate but to reach every student in his or her own wonderful, idiosyncratic place—and so it’s a profession where failure is inevitable. There’s a kind of accompanying guilt that can overwhelm. That becomes paralyzing.

So guilt is one of the challenges. Not specific to this semester, though certainly more pronounced. The challenge, as ever, is acknowledging it, while not allowing it to overtake the actual tasks at hand.

Tracking progress

The other challenges are more concrete, less emotional.

The first: oh my. Keeping track of things.

At the start of the semester, I gave students an optional progress tracker (modeled after one Emily Donahoe shared last year). But I belatedly realized that I needed some kind of tracker myself. So, a few weeks in, I created a spreadsheet to record student absences. Then the spreadsheet grew to include tardies. Then how tardy. Then it expanded to include columns for missed work (work submitted within 48 hours of the due date) and ignored work (work not submitted at all). Then a column for peer review. A column for incomplete work.

It’s less of a mess than it sounds. But certainly cumbersome.

The spreadsheet, however, is mostly about engagement. It does not contain what is most difficult to track: student growth.

I’m thinking of growth primarily through revision: Is a student engaging with feedback (from me, from their peers) and make substantial, effective changes from one draft to the next?

I realized, on the first assignment, that the working draft had faded from my mind by the time I read the second, polished one. So I’d have to go back to the first if I wanted to see how much a student had grown and revised.

I had students reflect on their changes by creating a table where they copy-and-pasted feedback from the working draft, the part of their working draft it corresponded to, the change that they’d made in the polished draft, and a brief explanation of why they’d changed it.

In theory, I could read across the table, see what they’d done (or tried to do) and the extent of their revisions. In practice, this was somewhat true, but there were a host of problems. First, many students copied the entire comment and then paraphrased what they’d done, making the table hard to read and the specific change still unclear. Second, the assignment (an initial description of their research) was not necessarily given to a ton of revision, so even when I was able to follow the changes students had made, they weren’t, in most cases substantial.

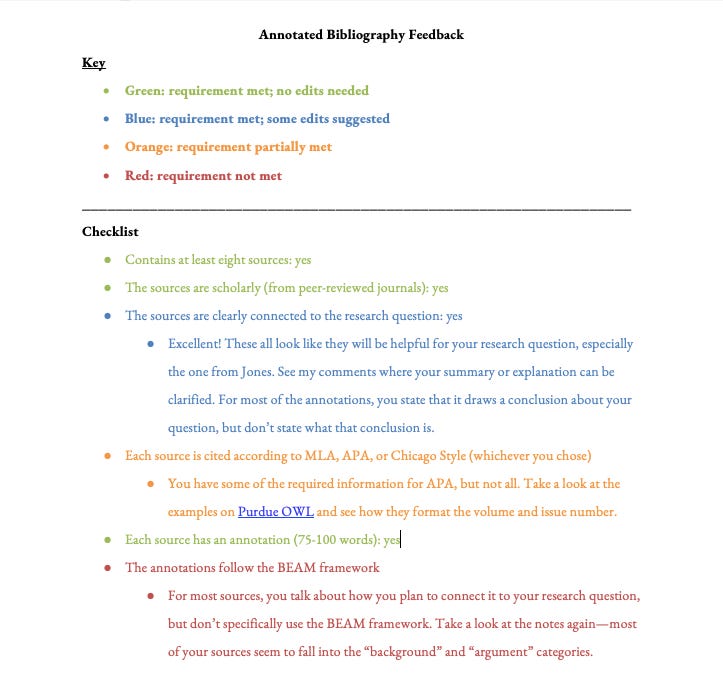

Modifications: I’m going to keep the reflection-table assignment for future writing projects, but I’ll model it again to show students what I’m expecting. I also adjusted how I gave feedback for the second assignment (an annotated bibliography) to make it easier for the students to see where to focus their revisions and for me to compare drafts. I copied-and-pasted the checklist of the assignment requirements, color-coded them to show if students were meeting or not meeting each, and offered marginal feedback on the papers. Now, when they revise, I can quickly look at the checklist (much in the way I used to look at a rubric for a revised paper) and see if there’s been growth in any of the areas I noted on the working draft. It also means I won’t waste time revisiting an area the student already met on the working draft.

Midterm grades

I’ve been meeting with students for conferences this week and last, focusing mostly on their research, but at the end, we’ve turned to their progress in the class. We’ve looked at the grading contract, talked about goals, and then discussed the inevitable: What grade should they get for the midterm?

The conversations themselves have been going fine, but I’m uneasy about the way the course structure perhaps skews grades higher at midterm than they might be for the final. This would likely be true regardless of the alternative grading system, but it feels harder to articulate that without a numerical framework. At this point, students have submitted a polished draft of their “Initial Project Description,” which I would have graded pretty generously in any circumstances. And they’ve only submitted a partial working draft of the next core assignment, an annotated bibliography—which I would have graded for completion even in a traditionally graded course. So there isn’t much, growth- and revision-wise to consider for a midterm grade.

I’m anticipating students having more challenges with the second half of the course, because we’re moving beyond what they’re planning to do and into actually doing it . The later assignments—an annotated bibliography, research proposal, and the paper itself—will require more substantial revisions. So it’s likely that these assignments are the ones that will ultimately determine students’ final grades because they are the ones that will get at the questions about growth (Did the polished draft meaningfully incorporate feedback and improve from the working draft?) and the base requirements of each assignment (Did the polished draft meet or exceed the requirements?)

Some of my old feelings towards grades lingers, and (rightly or wrongly) I can’t shake the thought that a high midterm grade might make students complacent—just when complacency stands to be the most detrimental.

Modifications: I’m planning to have an honest conversation with students prior to the next assignment about the mid-term grades. We’ll also circle back to the concepts we started with: growth, risk, revision. We’ll revisit the grading contract and talk about the expectations for revision for their current project, and I’ll explain (and ideally model) what “substantial” revision looks like.

Questions

I still have tons of questions, but there are a couple that have been particularly persistent.

First, scalability: I can keep much of my students’ work in my head because there are only 26 of them. And for this semester, that’s all I’m worried about: Does this kind of grading work for one class of 26? But in the back of my mind is the nagging question of scale. And I know, in its current form, the kind grading system I’m using is not something I could do well with 50 students, let alone 100.

I’m not saying that it can’t be done at all—with alterations, with tweaks. Or that other instructors might be able to scale up in a way that I don’t think I’d be able to. But I have my hesitations.

This matters to me most as a former high school teacher. I’m curious about what alternative grading would (or does) look like at the secondary level, where most teachers have upwards of 100 students. Would this kind of system work for them?

Second, writing and research skills: I’m also worried that certain skill deficiencies are going to slip through. I didn’t care so much about this with the first assignment, which was more about getting initial ideas on paper, but now that we’re on to annotated bibliographies, I wonder if the students will focus enough on the feedback I’ve given. If the goal is growth—will their writing actually improve from the working to the polished draft? And, especially with an annotated bibliography, will that growth focus on larger concerns—or surface-level ones that are easier to fix?

I realize that this is the question I’m asking in the first place. It’s the question for the entire semester, so it’s unreasonable to expect to feel comfortable and confident in an answer already. But still.

Perhaps I’m sharing some of the impatience my students are feeling right now with their own research questions. In the thick of it, it’s natural to desire a quicker, clearer answer. It’s also tempting to imagine some kind of impossible perfect, where I’ll find the exact right way to grade (and teach and write and everything else). And of course, I won’t. In the end, I imagine I’ll have what I hope my students do too: an answer of sorts, but also new and more interesting questions to carry us forward.