One of my regular assignments this semester is an “aesthetic blog” on various craft elements, completed at the end of each unit. I’ve decided to share a version of these blogs here. The post for the first unit, can be found here. This unit, the second of six, focused on character and dialogue.

In my previous job as a high school teacher, I was the moderator for the students’ Creative Writing Club. We met after school once a week, workshopped when they had writing to share, spent time generating new writing when they didn’t, and, occasionally, did some mini lessons on craft. I’d usually ask them what they were working on and what they’d like to practice— invariably, dialogue was high on the list of techniques they wanted to get better at.

We looked at mentor texts and did some listening exercises, but overall I didn’t do an especially good job at helping them—in part because dialogue is something I struggle with too. As a reader, I can hear when it’s off: when it has that stilted quality that takes you out of the story, when it slows the pace down by detailing insignificant conversation, or when it incorporates too much clunky exposition. But as a writer, I’m not great at avoiding these pitfalls myself.

I realized, in the midst of class discussion this week, that when I think about dialogue as a writer or instructor, I think about mimesis: Does this seem like what someone would actually say? Does this resemble the flow of conversation in real life?

I don’t think these are bad questions, and they’re present for me as a reader as well, but dialogue (even highly believable, realistically rendered dialogue) is still always stylized. Always not quite how we talk—and thank goodness for that. Spend a few minutes transcribing a recorded conversation or podcast and you’ll realize how cumbersome it is to read a literal copy of human speech.

As a reader, I think I look for a degree of believability in dialogue, but also a kind of sound, that may play into the realism of a piece, but that also may nudge it in the direction of poetry, almost more like lines in a verse play than an imitation of how we actually talk.

In a writing lesson article for LitHub, “In Pursuit of the Gorgeous Sound of Language,” Ursula K. LeGuin describes the pleasures of sound, something she says we possess as children but often forget as adults. She is speaking about sentences in general, not just dialogue, but it seems particularly applicable to speech:

The test of a sentence is, Does it sound right? The basic elements of language are physical: the noise words make, the sounds and silences that make the rhythms marking their relationships. Both the meaning and the beauty of the writing depend on these sounds and rhythms. This is just as true of prose as it is of poetry, though the sound effects of prose are usually subtle and always irregular.

This is at least part of what I look for (or at least remember and love) as a reader when it comes to dialogue.

Take, for example, the following dialogue from Wiley Cash’s article “Craft Capsule: The Art of Active Dialogue,”

Original version

“What do you mean?” he asked, shrugging his shoulders nervously.

vs.

Revised version

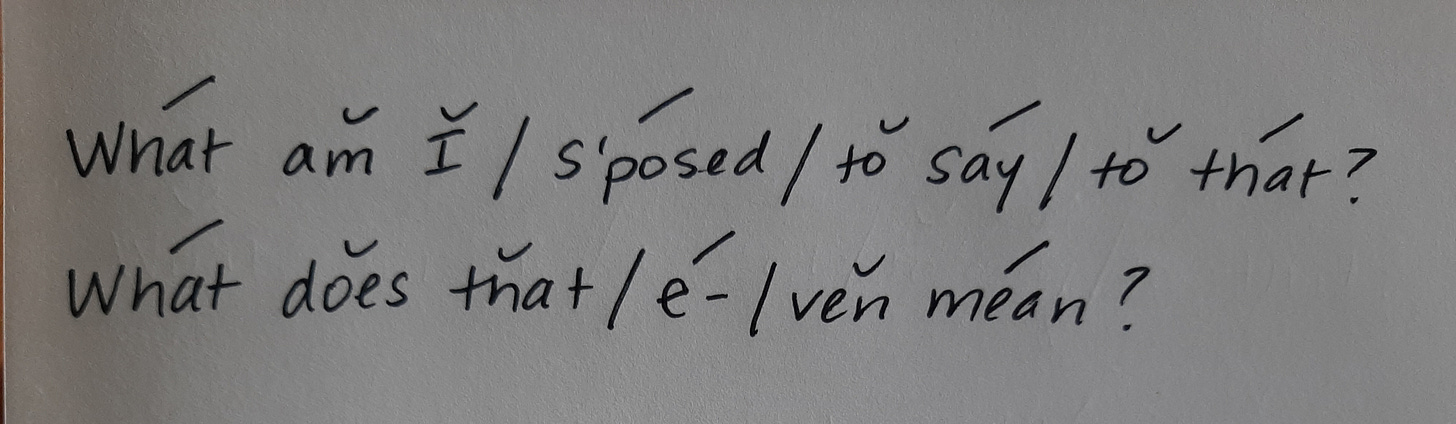

“What am I supposed to say to that?” He shrugged his shoulders. “What does that even mean?”

Cash is editing with an eye towards verbs and what he calls “stronger” dialogue—he’s not explicitly thinking about sound. He argues that writers tend to use gerunds and adverbs when the dialogue itself is weak.1 The result is an action with an ambiguous relationship to time (when does the “shrugging” begin and end?) and a sentence that asks the reader to simultaneously hear the dialogue and picture the action at once. In the above example, he edits the original version to strengthen the dialogue: the two questions in the revised version are more precise and loaded than the vague “What do you mean?” in the original. He also changes the gerund to a past-tense verb, separating it from the dialogue and situating it more clearly in time.

On a conscious level, this has nothing to do with the sound LeGuin was advocating for. But it’s present in his editing choices nonetheless. There’s a different rhythmic feel to untagged dialogue, to dialogue that is punctuated by sentences of action. Cash’s revisions create a rhythm, distinct from the original, through repetition and stress. “What” and “that” are repeated in both questions. And there’s a similar stressed-unstressed pattern in the two questions too, if you read supposed as s’posed, which is how I hear it in my head:

I think Cash is doing intuitively what good writers of dialogue do. Good dialogue does more than drive the plot forward or create dramatic tension. There’s a forward drive in the syntax as well, a meter that propels the reader on as much as the content does.

“Zikora”

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Zikora”2 is a dialogue-rich short story that warrants an entire essay or post on its own. But from both a sonic and character standpoint, there’s a particular conversation that struck me, that illustrates the kind of rhythmic dialogue I’ve been trying to describe above. It takes place between the narrator, Zikora, and her partner, Kwame. She tells him she’s pregnant, expecting a joyful reaction and gets, instead, a very different one:

On the day we broke up, we went back to my apartment after the gala, and I told Kwame, “So I’m very late and I’m never late.”

He looked confused.

“I might be pregnant.” I was so certain of his delight that I made my tone playful, almost singsong. But his face didn’t relax, instead it went still, as though all his features had paused, and suddenly this communicative man retreated into the cryptic.

He said, “We’re at different places in our lives.”

He said, “I’ll take care of everything,” in a voice that belonged to someone else, in words that he had heard somewhere else. Take care of everything. How absurd; we were both lawyers, and I earned a little more than he did.

He said, “It’s a shock.”

I said, “You came inside me.”

He said, “I thought you let me because you had protection.”

I said, “What are you talking about? You know I stopped taking the pill because it made me fat, and I assumed you knew what it meant, what it could mean.”

He said, “There was miscommunication.” (229, bolding mine)

This dialogue sounds to me like a real conversation—but also not. The repetition and gaps create a rhythm that is more sonically pleasing than the rhythms of actual speech. There’s the parallel structure and repetition in “So I’m very late and I’m never late.” The short, declarative sentences. The repeated tags (“He said” and “I said”) at the start of each sentence.

Aside from the pleasures of the rhythms Adichie creates in this passage, the sounds and silences are working to characterize Zikora, Kwame, and their relationship. For Zikora, there a shift from her singsong “So I’m late and I’m never late” and even the clarifying “I might be pregnant” to the short, “You came inside of me,” and the longer flow of sentences at the end. The return to parallel structure in her final words— “what it meant, what it could mean”—now conveys shock rather than playfulness. Her speech moves from joy to confusion, and it’s the sound and structure that captures this as much as the content of what she says.

Then there’s the starkness of Kwame’s statements, made more stark when the sentences stand alone. The characters in this scene are isolated from one another, and their dialogue reads like that too. They are responding to, but not understanding, one another. The dialogue on the page looks disconnected—and it sounds that way too.

The tension of this scene, to me, lives in the silence between the character’s speech, in Zikora’s lack of commentary in the middle and end of the passage. As a reader, I feel (and hear) her shock in the blunt rhythm of those lines, the way the words are hitting her.

The scene leaves me thinking about how so many parts of fiction are bound up in one another. About how something like sound—which could seem like poetic excess in prose, a sort of frosting that’s nice but not necessary if you have a really good cake—can contain so much of what’s essential to a story. Character, dramatic tension, affect. These are things to be understood and felt, but also—as LeGuin says and Adichie illustrates—to be heard.

I’d long internalized the writing “rule” about adverbs, but Cash’s focus on gerunds was new to me. The adverb admonition puts me in mind of Stephen King’s advice in On Writing. “I can be a good sport about adverbs,” he says, “With one exception: dialogue attribution” (125). He later criticizes the pratice of “shooting the attribution verb full of steriods” to produce tags like “Jekyll grated,” “Shayna gasped,” and “Bill jerked out” (126). King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Scribner, 2010.

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozie. “Zikora.” The Best Short Stories 2022: The O’Henry Prize Winners, edited by Valeria Luiselli. Anchor Books, 2022, pp. 221-252.

I'm usually writing my dialogue based on how the people around me talk, but sometimes I know I can write it better than they say it. I am especially going to keep rhythm in mind. Thanks Jane