The second draft

On rewriting a novel

Ann Patchett has a butterfly metaphor that I’ve mentioned here before, but it’s been on my mind again lately as I’ve been revising the novel. It goes like this:

A story is like a live butterfly, big and beautiful while it’s in her mind, but as soon as she commits it to paper, she kills it. Writing the story is a necessary death, one that she has learned to “weather” over time, but still—an act that she forestalls as long as possible.

She puts it much more beautifully:

The book is my invisible friend, omnipresent, evolving, thrilling. During the months (or years) it takes me to put my ideas together, I don’t take notes or make outlines; I’m figuring things out, and all the while, the book makes a breeze around my head like an oversized butterfly whose wings were cut from the rose window in Notre Dame. This book I have not yet written one word of is a thing of indescribable beauty, unpredictable in its patterns, piercing in its color, so wild and loyal in its nature that my love for this book, and my faith in it as I track its lazy flight, is the single perfect joy in my life.

[. . .]

When I can’t think of another stall, when putting it off has actually become more painful than doing it, I reach up and pluck the butterfly from the air. I take it from the region of my head and I press it down against my desk, and there, with my own hand, I kill it. It’s not that I want to kill it, but it’s the only way I can get something that is so three-dimensional onto the flat page.1

I’ve been turning this image over in my mind, and I’ve landed on three things:

The live butterfly of my story resides, not in the imagined space of my mind, but in the language on the page.

There are several ways to kill a story.

Half of revising lies in trying to find a way back to the living story, in attempting to resurrect it.

This is different than the point Patchett is making in her essay—but the way she frames her process has given me some language to think about my own. I’d like to try to describe some of that below, borrowing her metaphor and playing with it a bit. I’m new at this, so the process—as well as my thoughts about it—are flawed. But I want to get them down if only to fully see what they are—and perhaps hear how others have gone about novel-writing as well. (Have you done this? What’s it been like? I’d like to know.)

Finding the story

I have written, already, a first draft of the novel—what Matt Bell calls “the exploratory draft.” There are other names for early drafts that similarly grant permission for writing to be imperfect—Anne LaMott’s “shitty first draft” or, more grotesquely, as one of my neighbors just told me, a “vomit draft”—but I like “exploratory draft” because it conveys, at once, a sense of both wandering and direction. You are in a place you have never been before, but you are looking. You are writing with purpose. You don’t know the route, or even where you will end up, but you have a sense of the story you are trying to find.

When I wrote this first draft, I did some shitty “free-writing” along the way—some stream-of-consciousness style writing, some quick writes to get words on the page, stuff I knew wouldn't actually go in the draft. But the draft itself was something I was crafting as I went along, editing and workshopping and shaping, even though I didn’t quite know what I was writing my way into.

So I didn’t have a period of time, as Patchett did, where the book lived whole and beautiful in my head. I was finding it on the page, and oftentimes, the words themselves were how I was finding it—in the very beginning, the logic of the story often lay as much in how one sentence or image related to another, as it did in how the characters moved about in a scene.

Because the word “exploratory” also grants a lot of permission. When you’re exploring, you can follow certain impulses. You need to get somewhere, eventually, but when you don’t know where that is yet (or, when you don’t know how to get there) you end up looking at a lot of things along the way.

There are frustrating moments in this as well. You get lost. You spend time going down a track you really didn’t need to bother with. But—apologies for the mixed metaphor, butterflies and now meandering trails—as a whole, this is a lively, exciting time.2 You are finding the story, and everything, beautiful or ugly, that you encounter, is new.

To modify Patchett’s metaphor: In this kind of first draft, you’re actually living in the land of the story, tracing its paths past lakes and alongside boulders and near creeks. The sentences are stretches of steps. Paragraphs little hills.

Mapping where you’ve been

And then, you finish the draft.

I was worried, when I found myself midway through the first draft, a bit lost in it, that the end might be a bit of a death. I thought it might feel the way that arriving at the end of a pilgrimage or long journey often does: The whole point was to get there, but once you get there. . . you don’t know what to do. Even though I’d written short stories and ought to have known better, I felt as though, with the enormity of a novel, the full draft would be a fixed thing: Once I wrote it, I would be stuck with it, a kind of solid, immovable block. I could toss it or hack away at it, but it would be unavoidably. . . there.

Matt Bell, in his book Refuse to Be Done, describes the later stages of drafting quite differently than this, starting by recognizing what the first draft is: not the novel itself, but a map of it:

. . . the first draft isn’t the book I’m writing, only a sort of one-to-one scale model of it, not the novel itself but an idea of what the novel could be. I always think here of the Jorge Luis Borges story “On Exactitude in Science,” where a country’s caste of cartographers pursues accuracy and excellence to the point of creating a highly detailed map exactly the same size as the country, an impressive but entirely useless artifact.

. . . the first drafts of my novels have never been the real thing, only full-scale suggestions of what they might become. Book-size maps of books.3

The process of revising—or, more properly, rewriting—the novel is therefore much more creative than chipping away at some solid form. There’s still a good deal of discovery left, after that first draft: Now that I’ve traveled this ground, what, exactly, do I have here?

Bell’s suggestion, upon finishing the first draft and letting it sit for a time, is to outline the existing draft: to create, essentially, a more usable map of what you’ve already written. He suggests writing this as a narrative outline: an outline in the style and voice of the novel, so that it feels less like outlining and more like actual writing.

I decided to try this in October. I had been at the residency for a month, and after spending September doing background research for the middle of the novel, I knew I had to switch to writing, so I’d given myself a deadline: October 1, I would start. I had already listened to Bell’s audiobook back in December and planned to use his approach as a bit of a template this year, starting with this step.

It was a weird beginning for me. I am not in the habit of outlining stories—outlines have never made sense to me because I think of them as a pre-writing activity, something writers do who like to plot out their stories in advance, which is not how I write.

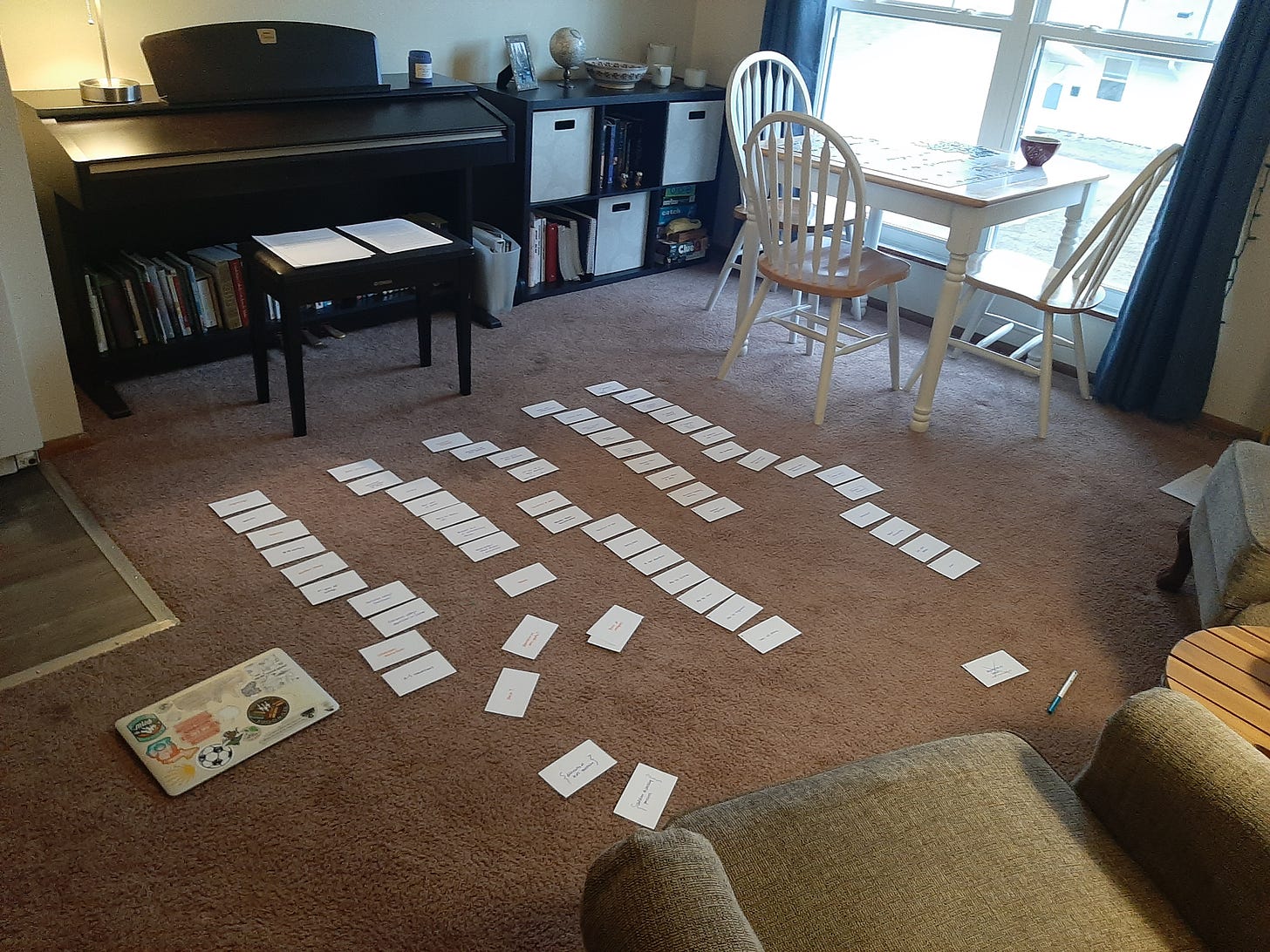

I have cut up stories into pieces after they’ve been written. I’ve distilled parts onto notecards so that I can arrange them or move them around. My apartment occasionally looks a bit insane when I’ve done this to the walls. Or just a bit cluttered when the papers occupy the floor. But a full outline? No.

Bell’s approach felt more appealing to me because: (a) the novel was already drafted—this was retrospective. I was describing what I’d already written, not plotting out where I’d go, and (b) the “narrative” approach (however odd it might feel) would hopefully get me back into the language of the story.

This was the part I was most worried about. I was so sick of the novel, had been mostly avoiding it for months, and every time I opened the document to peek at it, the language, was, well—worked over, uninteresting, dead. I’d been traveling that ground and now it was, yes, just a map. Never mind that the words were exactly the same as what I’d originally wrote—the experience of writing them, of getting them onto the page, and the experience of rereading them was very different.

I won’t go into all of the details here except to say that the narrative outline did exactly what it needed to do: It eased me back into both the story and its language. I wasn’t able to write in the voice of the novel for the outline, but in trying to, I felt a desire to return to the novel that I hadn’t all summer.

I also realized, immediately, some very basic plot questions that I’d failed to ask in over a year of working on the same story. Though this is not something Bell recommends, I found myself, when confronted with moments like this, moving fluidly from outlining into writing new scenes, because I was already half in the language already.

The outline went surprisingly quick. I thought it would take weeks; it took days.

But then I found myself stuck again. The next step that Bell recommends is revising the narrative outline. Which was now the kind of outlining I do not like. So I avoided it. I worked on a few other projects, went back to research, played with the scenes I’d written. I made a timeline on my whiteboard. I went for some long walks and tried to let the story take up imaginative space in my head.

Revising the outline is a step that makes so much sense—it’s more manageable than revising the unwieldy draft. The draft is right there, in the outline, in miniature, ready to be fixed. And then you would you know, going back into the novel, where you were going.

But if the first draft was just a big, billowing map, then the outline was something even less than that. A little pocket-sized thing, a sketch. I couldn’t keep staring at a drawing of where I’d been. I didn’t want to plot a new route through the landscape of the novel at a distance.

I wanted to go back, map in hand and see if could find a path from inside of it.

I wanted, not the partial language of the narrative outline, but the real language of the story itself.

Returning

So I skipped to Bell’s next stage, which is: retyping.

I’d done this before, actually, back when I was preparing the first draft of the novel for the thesis defense in February. The first third of the novel was one that I’d workshopped and revised several times, and I’d already read Bell’s book at that point, so when I revised the draft ahead of the defense, I did a bit of a scattered approach, given my time constraints. I polished the last third, rewrote the middle—and retyped the first 100 pages.

The idea is this: You work from the initial draft, physically retyping (not copy-and-pasting), so that you naturally edit as you go along. I found, when I did this last winter, that I tended to edit on the level of scene when I did this, but not on the level of sentence, so when I started in October, I also added what I usually do when I’m revising a short story: I began the day by reading the section out loud.

In Bell’s approach, you’re using the narrative outline as a guide. I had the questions and scenes that my outline had produced, so I reviewed these right before I started, but otherwise—I didn’t look at the outline itself.

And then. . . there I was, back in the language of the story. It was, I suppose, like any time you return to a place you’ve traveled before. Which is to say: full of surprise and recognition. There are pieces you’ve forgotten until you encounter them again, and immediately remember. Nothing is as magical as it was the first time, but you can see certain things more clearly because you know where you are going. And—this is the fun part—you can stop, pause. And take a different path.

This is the frustrating part too, because most of these paths feel forced. You didn’t take them the first time, and they feel unnatural when you do now, but you try it anyway, hoping it will break into something that feels right. Sometimes it does. Sometimes, in the end, the first path was right.

But in both the rote retyping and the new writing, there are moments when the story feels alive again, where it’s not a dead map, where you have, actually, found your way into the real place again. Where you think there might even be a deeper place past it.

Keeping the story alive

I love writing, but I will admit: A lot of it is drudgery.

And so part of a long project, I think, is finding little ways to keep it alive. And being wary of things that might kill it—trying to protect it a bit.

For me, fixing a story in place too much kills it. I need at least a little bit of play, a little bit of discovery, even in a redraft.

Another method of killing writing comes from talking to people too much about it. I think this is probably true for most people. I can do it. I’ve gotten through an hour-and-a-half of thesis defense doing so—and found this to be, actually, enjoyable. But in most contexts, with most people, the kind of summarizing such conversations entail feel akin to outlining. They are so far removed from the story itself, so distant from its specifics. . . To return to Patchett’s butterfly: It’s like catching the creature in the air and touching fingers all over its wings. It might not kill it, but it’s certainly not doing it any good.

My first week here, after I fumbled an answer to the question of what I was working on at a gathering on campus, a well-meaning professor told me I needed to work on my elevator pitch.

“You don’t,” a friend told me later. “You aren’t selling anything.”

She was right. I’m not—but I knew I would get the question again, that it was, in part, a payment for being at a writing residency, getting asked this. And, what’s more, I want to have meaningful conversations with people about our work here. I won’t be in workshop this year—I won’t be sharing my writing with anyone—so I if I was going to talk about it, I had to find a way that I would be comfortable with, a way that protected it, but also opened it up. So I practiced what I could say; I revised. I found a wording that shared the parts of the novel that I wanted to talk about.

I’ve adapted this, over time. It’s different with people who are passing aquaintances, people who are staying here for the year.

And, in my writing, which has had several ups and downs this past week, I’ve been trying to come back to new language when I’m feeling stuck—to let just a small piece of it unfold again new. To see where that path might take me.

Patchett, Ann. “The Getaway Car.” This is the Story of a Happy Marriage. HarperAudio, 2013.

Apologies for the multiple muddled metaphors in this post—but also, I still stand by my defense of mixed metaphor/simile, and think that maybe (maybe?) it’s fitting for the butterfly to float about on the trail. None of this is logically clean, but I wonder if there’s a sort of sense to be found in it nonetheless.

Bell, Matt. Refuse to Be Done: How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts. Soho Press, 2022.

Love this update! I hadn't heard of Matt Bell's book before and I'm running to pick up a copy. I personally love your map metaphor, and the concept of rewriting vs. revising really resonates with me as I barrel toward finishing my first draft. Happy rewriting to you! I hope you continue to uncover lovely surprises along the way.