One of my regular assignments this semester is an “aesthetic blog” on various craft elements, completed at the end of each unit. I’ve decided to share a version of these blogs here. The post for the first four units can be found here, here, here, and here. This unit, the fifth of six, focused on genre and structure.

500 Days of Summer was released when I was a senior in high school. I vividly remember going to see it in theaters with a couple of friends, debating the ending as we walked out into the parking lot, the sun blindingly bright in the way it always is after exiting the dark space of an AMC.

The movie begins with an overture of the two central characters, Tom and Summer: their beliefs about love, their childhoods, the day that they meet. An authoritative, bodiless narrator provides a voiceover throughout, concluding with two claims about the story we’re about to see: “This is a story of boy meets girl. But you should know upfront: this is not a love story.”

Regina Spektor’s “Us” plays; parallel images of the characters as children unfold on either side of the screen; and in spite of the words we’ve just heard, we’re primed for the conventions of the romance genre—namely, the converging of two lines, the movement forward in time towards a singular, unified end.

So often, in love stories—the romance genre, but also the stories people craft about their own love lives—timing is at the center of it. The random encounter, the unlikelihood that two people would cross paths at the moment they do. But, alongside that, is the sense of ill-timing, of moments missed, of paths crossed at exactly the wrong moment in time. That phrase, so often bandied about, “The timing just wasn’t right,” suggests, not that the pairing of two people is wrong, but rather that the time of their meeting was.

I distrust that statement; I think it’s often just a simpler, more palatable way to deal with life’s ambiguities. But it does suggest something true: that the way we narrate and make sense of things is bound up in our sense of time, in the way we inscribe a particular moment into the larger narrative of our life. And this shifts depending on our vantage point. We might move through time linearly, but that doesn’t mean that we narrate it so.

500 Days of Summer speaks into that. It’s not the timing of Summer and Tom’s meeting that is wrong—they’re both single, and though Summer is oh-so-typically “not looking for anything serious,” she marries another man by the end of the film. The timing is not wrong—they are (to substitute one cliche for another) simply wrong for one another.

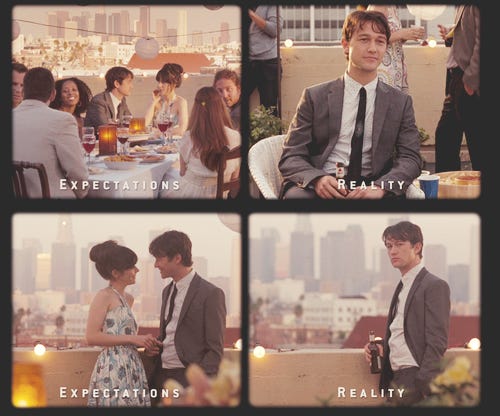

The movie is interested, not in the linear timeline of their relationship, but in the timing of narration, the ordering of events in Tom’s memory. And so the story unfolds in an entirely non-linear fashion, jumping from day to day, signaling the point in time by a graphic of a tree with the day of their relationship (1-500) in parentheses. We jump from happy moments between them, to the break-up, to the moment Tom decides to win Summer back. Until, finally, we reach the moment when Tom realizes he will be unable to do so, in a scene that again makes use of parallel screens to juxtapose his imagined narrative of the evening with the one that actually unfolds. By the end of the night, he realizes Summer is engaged, that it’s not a matter of convincing her of the realities of love—she believes in love, just not with him.

From a narrative standpoint, one of the most instructive moments of the film is when Tom’s younger sister prompts him to look back, to view things differently. “I think you’re just remembering the good stuff,” she tells him. “Next time you look back, I really think you should look again.”

This prompts a new remembering from Tom, a play of scenes across the screen from earlier in the movie, but now in a different order, with the negative ones—the ones of Summer’s distance and withdrawal—placed alongside one another, and then, finally, an omitted scene of Summer crying at the movie The Graduate. The omitted scene doesn’t offer any straightforward explanation of the break-up—but it does supply missing context for her emotions heading into the scene that immediately follows it: her breaking up with Tom in a diner.

In short, the reordering of scenes presents a narrative of a relationship falling apart, rather than of two people coming together. It shows how Tom’s earlier ordering of events was not a given structure, but a choice born out of his desires, the meaning he wanted to impart to the relationship.

The narrative restructuring points to the importance of timing, placement, and genre. Throughout the film, Tom has been trying to circumscribe the moments with Summer into a romantic arc; now, prompted to visit the moments again, he does not eliminate the happier moments, but sees them in new relation to the sad, tense, or distant ones. The vantage point from which he narrates—within the relationship, or out of it; with an insistence that Summer was “the one,” or with a recognition that she will not be—changes the order that makes sense to him, the one that reveals the meaning of the relationship as he understands it at a specific point in time.

I think about this often. Not just in writing, but in terms of internal narrative. That an event often means one thing to us while we’re in it, another thing to us in the immediate aftermath, and another thing entirely years down the road. In part because of perspectival distance, but also because we can put that singular event into conversation with any number that follow.

It’s not that meaning is absent in these moments, but rather that meaning shifts. It reveals itself, again and again. The most powerful moments of our lives are not static; they continue to make meanings over time. In the essay “The Experience Between: Thoughts on Nonlinear Narrative,” Adam Braver remarks:

It’s the pieces—their arrangement and the space left between them—that tell a story. It’s about navigating an unfamiliar world with some sense of predictability, while accepting that underneath the surface meaningful experiences are happening in the most natural, least explanative way. (107)1

I like the paradox of that statement, the sense that predictability and inexplicability coincide, that things can be familiar and unfamiliar at once. I think that’s what 500 Days of Summer is doing, at its heart: playing into all the familiar, recognizable moments of a romance that is both promising and unfulfilled, showing all the failed and flawed ways we can read a relationship when we’re inside of it and long after we’re not.

And then there’s the ending. As a cynical teenager, I had a dramatic reading of the movie’s final scene, shaped less by the film itself and more by my desire for it to challenge the Hallmark narrative arc more than it ultimately did. In the last scene, en route to a job interview, Tom encounters a woman and asks her out. After first saying no, and then saying yes, she reveals her name—Autumn (immediate cringe)—and the screen flicks to the tree image. The number rolls back from “500” to “1” and the tree bursts into bloom.

I hated this ending. I felt like it undermined everything the rest of the film had been doing, all of the ways it had been complicating the typical romantic comedy and narratives of love. The ending catered to what the audience wanted; it wasn’t bold enough to conclude on a more pessimistic or ambiguous note.

I wanted the movie to end with one of the earlier scenes: with Summer telling Tom he had been right about love, and him telling her he’d been wrong, the two of them switching perspectives. Or with Tom walking into the job interview, the possibility of a fulfilling career on the horizon. (I have problems with this now that I didn’t at the time—moving a person’s worth and happiness from romantic fulfillment to job. But at the time I thought it would be a good ending.)

Instead, the movie ends as most romantic comedies begin: with a meet-cute that we are set-up to read as the beginning of a wonderful romance.

A happy ending, my friends argued. He finds love in the end; it just wasn’t Summer.

A delusional ending, I thought. He’s in the same position as he was before: thinking he’s found love. He’s about to enter the same narrative arc that he just exited.

I think there is validity in my reading—but also my friends’. The ending that I so hated when I first watched it is more complex than the ones I envisioned, in part because it leans into the way that timing shapes our narratives. Without the perspectival distance from Tom and Autumn’s meeting, we don’t know how to read it—they don’t know how to read it—and it is this ambiguity that makes love stories, in spite of their tendency towards genre conventions, so compelling. The predictability of the typical rom-com makes it easy to forget that we don’t know—even when we feel, as Tom did with Summer, that we do—how the events of our life will unfold.

The ending is fitting precisely because it could be Tom finding love or it could not. The ending is not about knowledge—it’s about Tom accepting, at least on some level, narrative ambiguity. Summer, by the end, has ascribed to the Hallmark-style narrative, focusing on the unliklihood of her encounter with her now-husband, the certainty about him that she feels now. But that’s mostly, if not entirely, a product of her vantage point: she believes this narrative because she can fit the events of her life into it now.

Tom, who is ready to foresake his former romantic worldview and adopt Summer’s position that love is a fantasy, cannot fully do so. Nor, however, can he make them fit the cynical view that Summer evinces throughout the film: that love doesn’t exist. He knows that it does—he knows how he felt—and he’s uncertain enough about the future to wonder where the narrative of this next love story might go. The cheesy image of the tree bursting into bloom at the end isn’t an omniscient commentary on the promise of the relationship, or an indication that Tom and Autumn are entering into a season that will necessarily end. It’s a sign of what the moment means to him at present, and a reminder that it will look different depending on how the future unfolds, the events he places it alongside later on.

Nonlinear Narrative and Creative Process

From a writing standpoint, this emphasizes to me how much a narrative changes based on the order of events. The way that we understand something depends almost entirely on its relationship to time.

In class this week, we did an exercise with Alice Munro’s story “Royal Beatings.”2 We numbered the sections—four in total—described them, and then considered how the story would change if we shuffled the order. The narrative is nonlinear already, with both the past and the future interrupting the main time of the story, in which the character Rose awaits an impending beating from her father at the request of her stepmother Flo. The first section, in which the beating and characters is introduced, gets interrupted with a foray into the past, which illuminates both the family’s history and the role of violence within the town where they live. As a result, we experience Rose’s predicament first as an isolated, personal event, and then as one indicative of a broader societal tendency. The interruption also creates suspense, prolonging the moment of violence against Rose as we wait, for pages, to return to this point in time. The end jumps far into the future, with Flo in a nursing home, a moment that shifts the view of her character and reframes the moment of Rose’s beating from a perspectival distance.

The order changes everything. The sympathy we grant or withhold from characters. The way we focus on the specific violence within Rose’s family or the larger, societal violence of the broader community. Rendered linearly, the story would not only lack impetus, it would suggest that such an ending is inevitable. Rendered as pure retrospection (starting in the future, with the nursing home, and looking back) Flo might be far more sympathetic than she ought to be. There would be movement in time, movement in action, but not movement in understanding. As it is, each section of the story sets the reader up to understand a moment in one way, then reframes it by situating it in relation to another point in time.

Braver recommends this kind of thinking as part of the creative process: literally taking scissors to one’s work and seeing what the pieces look like rearranged. I’ve done this many times. With poems, with stories, with essays. There are cut-up pieces of an essay in my office as I type this, some taped to the window by my desk and some in a pile below. There is a story I worshopped this week that is begging to meet the same fate.

But beyond writing, I think this is something we naturally do in memory anyway: rearrange the events of our life in our mind, situate them in new relation to one another, trouble whatever understanding we initially had of their meaning. It’s a reminder, to me, of the inexhaustible narrative possibilities that discrete moments have, their ability to keep meaning long after we think we think we know what they say.

Brave, Adam. “The Experience in Between: Thoughts on Nonlinear Narrative.” The Writer’s Notebook II. Tin House Books, 2012, pp. 105-114.

Munro, Alice. “Royal Beatings.” The New Yorker, 6 March 1977, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1977/03/14/royal-beatings.